After I read some documentation about MPEG-1 Layer 1 again this week, I realized that I misunderstood some arguably important things about the difference between PASC and MPEG 1 Layer 1. So let me elaborate on that.

The MPEG standard (IEC/ISO 11172-3) defines that each frame of MPEG-1 Layer 1 (which I shall refer to as MP1) audio shall have the following number of slots:

N = 12 * B / S

Where:

- N is the number of slots per frame; one slot is 32 bits

- B is the bit rate of the encoded stream; for DCC this is 384000

- S is the sample rate of the audio; DCC supports 32000, 44100 and 48000.

So, for 32 kHz, each frame has 12 * 384000 / 32000 = 144 slots = 576 bytes. Each frame represents 12 ms of audio (144 * 32 / 384000).

For 48 kHz, each frame has 12 * 384000 / 48000 = 96 slots = 384 bytes. Each frame represents 8 ms of audio (96 * 32 / 384000).

For 44.1 kHz, the calculation results in a non-integer: 12 * 384000 / 44100 = 104.489795918 according to my calculator. The actual accurate result is 104 + 24/49. That means that:

When a 44.1 khz audio stream is encoded in MP1, the encoder must write frames that alternate between 104 and 105 slots (416 or 420 bytes), but every 49 frames, a 104-slot frame would be followed by another 104 slot frame, after which the alternation would continue.

So the frame lengths are [0]104 [1]105 [2]104 [3]105 … [46]104 [47]105 [48]104 [49]104 [50]105 [51]104…

The MP1 standard defines the padding bit in the header of an MP1 frame that indicates that the frame “contains an additional slot to adjust the mean bitrate to the sampling frequency”.

This bit is not well documented and unless you read and understand the standard document, it’s difficult to understand.

As it turns out, I interpreted it wrong.

Around 1996, I was on the DCC-L email discussion list (remember those?) and someone asked about whether it would be possible to convert the compressed data format on DCC tapes to something that could be played on e.g. a PC. I don’t remember the exact phrasing of the question but until then, I thought Philips had invented some sort of compression system that would be closed-source forever. But someone on DCC-L who worked for Philips said that PASC was basically the same as MPEG Layer 1. That was a bombshell!

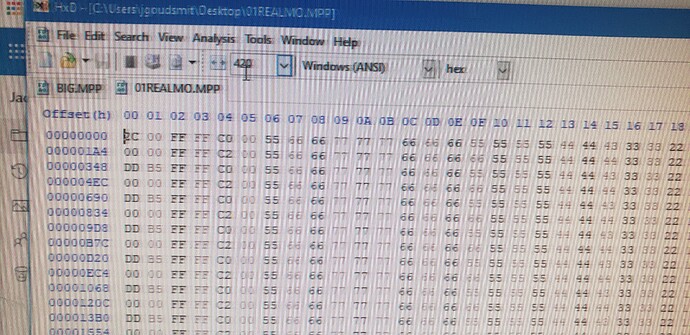

Someone else had figured out (or already knew) that the .MPP audio files of the DCC-Studio program could be converted to MP1 files that could be played or converted with an MP1 decoder. The program was written in Turbo Pascal and would read one frame at a time, check the bit in the header, reverse the bit if necessary and write the frame without the extra 32 zero-bits to an output file. I didn’t have a website of my own at that time, but someone else put it on their website so that anyone could download it and use it.

Unfortunately that website went offline sometime between 1997 and 2003. And I didn’t have a copy of that program. But in 2003 I came across the ISO/IEC 11172-3 standard and read it for the first time. I didn’t understand much of it in 2003. But I did finally find out what that mysterious bit in the header was for.

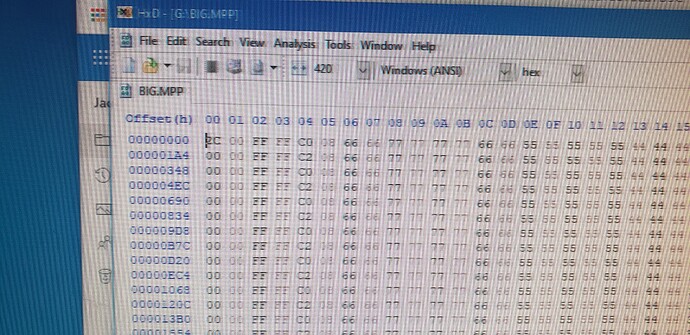

What I got wrong at that time was that I thought that the bit in the header meant that the frame had an extra slot of zeroes (if the bit was set to zero) so that all frames would end up being 420 bytes and the tape speed for DCC could be clocked from the data speed. After all, that’s what I had observed with the .MPP files that were used by DCC-Studio. But now I’m pretty sure it’s not true.

The bit in the header indicates that the frame has an extra slot with data at the end (if the bit is set to one), and this only happens for 24 out of every 49 frames. I’m pretty sure the extra zero-bytes are inserted into the .MPP file by the DCC-Studio program to make all the frames in the file 420 bytes and make it easy to seek to a particular frame. As far as I know, on the tape, PASC is encoded in the exact same way as MP1.

I’ll have to verify this with a logic analyzer, and if I’m right, I guess I’ll have to update some Wikipedia pages, and some other documentation…

===Jac